The term ‘evidence’ owes its origin to the Latin terms ‘evident’ or ‘evidere’ that mean “to show clearly, to discover, to ascertain or to prove”

According to Phispon

Evidence means, the testimony, whether oral, documentary, or a real, which may be legally received in order to prove or disprove some fact in dispute.

According to Taylor

Evidence is shown for the purpose to prove or disprove any fact, the truth of which is submitted to judicial investigation.

According to Advanced Learner Dictionary

Evidence means anything that gives reason for believing something that makes clear or prove something.

Evidence refers to anything that is necessary to prove a certain fact. Evidence is a means of proof.

Definition: Sec-3 of Indian Evidence Act, 1872: “Evidence” means and includes —

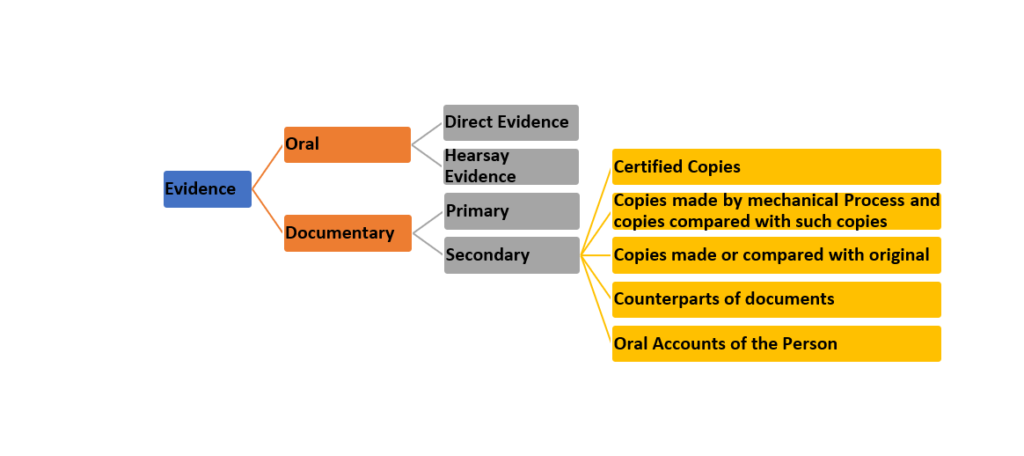

- Oral evidence: All statements which the Court permits or requires to be made before it by witnesses, in relation to matters of fact under inquiry,

- Documentary evidence: All documents including electronic records produced for the inspection of the Court,

Documentary Evidence (Secs. 61-90)

Documentary evidence means all documents produced for the inspection of the court. Documents are denominated as ‘dead proof,’ as distinguished from witnesses who are said to be living proofs.’ Documentary evidence is superior to oral evidence in permanence, and in many respects, in trust worthiness.

Sec. 61. Proof of contents of documents – The contents of documents may be proved either by primary or by secondary evidence. There is no third method of proving the contents of a document.

The contents need not be proved by the author of document, and can be proved by any other evidence.

Banarsi Das v Maharaja Sukhjit Singh AIR 1998 SC 179:

In the absence of the documentary evidence which could have been available, the plaintiff was not allowed to rest his case on oral evidence which was against the record produced by the defendants.

Section 3 Documentary Evidence: The expression “Document” means any matter expressed or described upon any substance by means of letters, figures or marks, or by more than one of those means, intended to be used, or which may be used, for the purpose of recording that matter.

Illustrations: A writing is a document; Words printed, lithographed or photographed are documents, A map or plan is a document; An inscription on a metal plate or stone is a document; A caricature is a document.

Narsinga Rao v. State of Andhra Pradesh, AIR 2001 SC 318 :

The Supreme Court held that in order to prove the documents original document is to be produced. Contents of it are to be proved so also signature on the same have to be proved. When document appeals to the conscious of the Court that it is genuine, contents of the same need not be proved.

Ravichandra v. M/s. Elements Development Consultants, Bengaluru, 2018 Cri. LJ 4314 (Kar):

The Court observed that mere marking of a document cannot be said to be the proof of said document. The document has to be proved in accordance with law and the same has to be appreciated in order to ascertain the genuineness of the document with other materials available on record. In that context, both the parties would get ample opportunity to counter those documents as well to submit their arguments with reference to the evidence already recorded by the court.

Kinds of Documentary evidence: There are two kinds of Documentary Evidence.

- Primary Evidence and

- Secondary Evidence.

- Primary Evidence

Definition : Sec-62

Primary evidence means the document itself produced for the inspection of the Court.

Explanation 1:

Where a document is executed in several parts, each part is primary evidence of the document; Where a document is executed in counterpart, each counterpart being executed by one or some of the parties only, each counterpart is primary evidence as against the parties executing it.

For example, in the case of a cheque, the main cheque is signed by the drawer so that it is primary evidence against him, and the counterfoil may be signed by the payee of the cheque so that it will be a primary evidence against the payee. Similar is the case of patta (executed by lessor/ landlord) and the qabuliat or muchilka (executed by lessee/ tenant).

Explanation 2:

Where a number of documents are all made by one uniform process, as in the case of printing, lithography, or photography, each is primary evidence of the contents of the rest; but, where they are all copies of a common original, they are not primary evidence of the contents of the original.

Primary evidence is the best or highest evidence, or in other words, it is the kind of proof which, in the eyes of the law, affords the greatest certainty of the fact in question. Primary evidence of a transaction, evidenced by writing, is the original document itself, which should be produced in original to prove the terms of the contract, if it exists and is obtainable.

Case Laws:

Narbada Devi Gupta v. Birendra Kumar Jaiswal, (2003) 8 SCC7459:

It was submitted that execution of documents is to be proved by admissible evidence and in a case where the document is produced and signature on the document is admitted, the document has to be read in evidence.

C. Purushothama Reddiar v. S. Perumal reported in AIR 1972 SC 608 :

The Court held the Plaintiff had admitted the signature on the carbon copy, hence, there was no further burden on the Defendant to lead any additional evidence for proof of the contents of the carbon copy.

Byramjee Jeejebhoy Private Ltd. v. Govindbhai A. Bhatte, and Others, reported in 1994(1) Bom. C. R. 21114 :

It was submitted that once the factum of the execution is proved, the document stands proved and it is wholly irrelevant whether the contents are proved or not.

Prithi Chand vs. State of Himachal Pradesh, 1989 (1) SCC 432

The Court held that since the carbon copy was made by one uniform process the same was primary evidence within the meaning of Explanation 2 to Section 62 of the Evidence Act. Therefore, the medical certificate was clearly admissible in evidence.

Md. Yakub Ali vs. State of Tripura, 2004 Cri. LJ 3315 (Guj) :

Where the post-mortem report is to be prepared in triplicate by pen-carbon and in the instant case also, the post-mortem report was prepared by pen-carbon in one uniform process and as such, in view of the provisions of Section 62 of the Evidence Act, such carbon copy is primary evidence.

Surinder Dogra vs. State, 2019 Cri. LJ 3580 (J&K):

The Court held that documents prepared under the uniform process of either printing or cyclostyle or lithography cannot be mere copies in strict legal sense of the term, in fact, they are all counterpart originals and each of such documents is primary evidence of its contents under Sections 45 and 47 of the Evidence Act. - Secondary evidence:

Secondary Document is the document which is not original document. Secondary Evidence is an alternative source of evidence other than original documents. Secondary Evidence is that such can be given in the absence of the Primary Evidence.

Secondary evidence means and includes—

- Certified copies given under the provisions hereinafter contained;

- Copies made from the original by mechanical processes which in themselves ensure the accuracy of the copy, and copies compared with such copies.

- Copies made from or compared with the original;

- Counterparts of documents as against the parties who did not execute them;

- Oral accounts of the contents of documents given by some person who has himself seen it.

Illustration:- A photograph of an original is secondary evidence of its contents, though the two have not been compared, if it is proved that the thing photographed was the original.

- A copy compared with a copy of a letter made by a copying machine is secondary evidence of the contents of the letter, if it is shown that the copy made by the copying machine was made from the original.

- A copy transcribed from a copy, but afterwards compared with the original, is secondary evidence; but he copy not so compared is not secondary evidence of the original, although the copy from which it was transcribed was compared with the original.

- Neither an oral account of a copy compared with the original, nor an oral account of a photograph or machine copy of the original, is secondary evidence of the original.

Ashok v Madho Lal AIR 1975 SC 1748; Govt. of A.P. v Karri Chinna Venkata Reddy AIR 1994 SC 591:

A Photostat copy of a document is admissible as secondary evidence if it is proved to be genuine; it has to be explained as to what were the circumstances under which the Photostat copy was preferred and who was in the possession of the original document at the time its photograph was taken. It can be permitted to be given in evidence when it is proved that the original document was in possession of adversary.

Union of India v Nirmal Singh AIR 1987 All 83

An uncertified photocopy of a government order cannot be given in secondary evidence. The value of Secondary evidence is not as that of primary Evidence. Giving Secondary Evidence is exception to the general rule. And notice is required to be given before giving secondary evidence.

Kinds of Secondary Evidence:

- Certified Copies

- Copies prepared by mechanical process:

- Copies Made from or Compared with the Original:

- Counterparts of Documents:

- Oral Accounts of the Person about the content of a document:

- Certified Copies: These are defined under Section 76. Section 63 declares certified copies to be permissible form of secondary evidence. S. 65(e) and S. 77 make certified copies of public document admissible in proof of contents of such documents. S. 79 raises a presumption with respect to genuineness of certified copy.

Copies of public documents other than those mentioned in S. 76 and in S. 77 may be proved in the manner described U/s 78.

Case Laws:

Manorama v. Saroj, AIR 1981 All 17

The Court held that a photostat copy of a document is not admissible in evidence. Only certified copy is admissible.

Suresh Banik v. State, AIR 1976 SC 1748 :

The Court held that a photostat copy of a document is admissible as secondary evidence if it is proved to be genuine. The genuineness is to be proved either by examining the photographer or by some other evidence.

Ashok v. Madho Lal, AIR 1975 SC 1748:

The Court held that in case of a photo copy of a document before it is admitted in evidence it has to be explained as what were the circumstances under which the photostat copy was preferred and who was in possession of the original document at the time its photograph was taken and that would be above suspicion.

State of Gujarat v. Bharat, 1991 Cr LJ 978 :

The Court held that a photograph can be proved by examining the photographer and by proving the negative.

Surinder Kaur v. Mehal Singh (2013)

The Court elaborating guidelines observed:- A photocopy of the original document can be allowed to be presented as secondary evidence only in the absence of the original document.

- When a photostat copy is presented as evidence, it is on the party producing it to prove that the original document existed and is lost or is in possession of the opposite party who failed to produce it. Mere assertion is not sufficient to prove it.

- After the photocopy is produced in the court as evidence, the opposite party must raise its objections regarding the non-existence of such circumstances or foundational facts at the earliest.

- When any such objections are raised, the authenticity of the copy must be determined as every copy produced from the mechanical process might not be accurate.

- Mere production of copy as the evidence does not amount to its proof. Its correctness has to be evaluated and proved independently. It has to be shown that it was made from the original document at a specific time and place.

- In instances where the photostat copy is itself suspicious, it is not to be relied upon, unless the court is satisfied that it is genuine and accurate.

- The genuineness of the copy is to be proved on oath by the person who made the copy or who can vouch for its accuracy, to the satisfaction of the court.

- Certified Copies: These are defined under Section 76. Section 63 declares certified copies to be permissible form of secondary evidence. S. 65(e) and S. 77 make certified copies of public document admissible in proof of contents of such documents. S. 79 raises a presumption with respect to genuineness of certified copy.

- Copies prepared by mechanical process:

The copies prepared by mechanical process and copies compared with such copies is mentioned in clause 2 of this section. In the former case, as the copy is made from the original it ensure accuracy. To this category belong copies by photography, lithography, cyclostyle, carbon copies. Section 62 (2) states that, where a number of document are made by one uniform process, as in the case of printing, lithography, or photography, each is primary evidence of the contents of the rest, but where they are all copies of a common original, they are not primary evidence of the content of the original. - Copies Made from or Compared with the Original:

Copies made from the original or copies compared with the original are admissible as secondary evidence. A copy of a copy then compared with the original, would be received as secondary evidence of the original. A copy of a certified copy of a document, which has not been compared with the original, cannot be admitted in evidence, such a copy being neither primary or secondary evidence of the contents of the original.

- Copies prepared by mechanical process:

- Counterparts of Documents:

A counterpart of document are primary evidence as against the parties executing them under section 62 and is secondary evidence as against the parties who did not execute it.

- Counterparts of Documents:

- Oral Accounts of the Person about the content of a document:

Oral accounts of a person about the content of a document must be closely examined. Not examining the informant or not presenting the report of that person is fatal and such a person’s report cannot be relied upon in such a case. This is last clause enable oral account of the content of a document being as secondary evidence. The oral account of the content of a document given by a person who has merely seen it with his own eyes, but not able to read it is not admissible as secondary evidence. The word seen in clause 5 of this section means something more than the mere sight of the document, and this contemplates evidence of a person who having seen and examined the document is in a position to give direct evidence of the content thereof. An illiterate person cannot be one who has seen the document within the meaning of the section.

Pudai Singh v. Brij Mangai,

Allahabad High Court held that as regards the letting in of secondary evidence the word “seen” in this section includes “read over” in the case of a witness who is illiterate and as such cannot himself read it, if it is read over to him, it will satisfy the requirement of the section. But this ruling was not accepted by High Court oral account of the content of a document by some person who has himself sent it. Oral account given by an illiterate person will be hearsay evidence and excluded by section 60.

- Oral Accounts of the Person about the content of a document:

When Secondary Evidence is Admissible ?

Section 65 : Cases in which secondary evidence relating to documents may be given :– Secondary evidence may be given of the existence, condition, or contents of a document in the following cases –

- When the original is shown or appears to be in the possession or power of the person against whom the document is sought to be proved, or of any person out of reach or not subject to the process of the Court, or of any person legally bound to produce it, and when, after the notice.

- When the existence, condition or contents of the original have been proved to be admitted in writing by the person against whom it is proved;

- When the original has been destroyed or lost, or when the party offering evidence of its contents cannot produce it in reasonable time.

- When the original is of such a nature as not to be easily movable;

- When the original is a public document within the meaning of Sec-74;

- When the original is a document of which a certified copy is permitted to be given in evidence;

- When the originals consist of numerous accounts or other documents which cannot conveniently be examined in Court, and the fact to be proved is the general result of the whole collection.

Secondary evidence, as a general rule is admissible only in the absence of primary evidence. If the original itself is found to be inadmissible through failure of the party, who files it to prove it to be valid, the same party is not entitled to introduce secondary evidence of its contents. Essentially, secondary evidence is evidence which may be given in the absence of that better evidence which law requires to be given first, when a proper explanation of its absence is given.

- In above cases 1, 3 and 4, any secondary evidence of the contents of the document is admissible.

- In above case 2, the written admission is admissible.

- In above cases 5 or 6, a certified copy of the document, but no other kind of secondary evidence, is admissible.

- In above case 7, evidence may be given as to the general result of the documents by any person who has examined them, and who is skilled in the examination of such documents.

Case Laws :

M.Chandra v. M. Thangamuthu, 2010 AIR SCW 6362:

The Court said that: “It is true that a party who wishes to rely upon the contents of a document must adduce primary evidence of the contents, and only in the exceptional cases will secondary evidence be admissible. However, if secondary evidence is admissible, it may be adduced in any form in which it may be available, whether by production of a copy, duplicate copy of a copy, by oral evidence of the contents or in another form.

The documents obtained under RTI Act can be admitted as secondary evidence, as they are obtained under a particular enactment, which fall within ambit of by “any other law in force in India”

Other Provisions regarding Primary and Secondary Evidence:

Secs. 65A/ 65B (Admissibility of Electronic Records in Evidence):

Section 65A and 65B have been added by the Information Technology Act,2000. Section 65A lays down that the contents of electronic records may be proved in accordance with the provisions of Sec. 65B.

Sec. 65B lays down that “notwithstanding anything contained in this Act, information in an electronic record which is printed on a paper, stored, recorded or copied in a computer shall be deemed to be a document and shall be admissible in any proceedings (without further proof or production of the original) as evidence of the contents of the original or of any fact stated therein of which direct evidence would be admissible.

It is further laid down that the following conditions have to be satisfied in relation to a ‘ “computer output”:

- Information was produced during the regular course of activities by the person having lawful control over the computer’s use.

- Information has been regularly fed into the computer in the ordinary course of the said activities.

- Throughout the material part of the said period, the computer was operating properly, or the improper operation was not such as to affect the electronic record or the accuracy of its contents.

- Information contained in the electronic record reproduces or is derived from such information fed into the computer in the ordinary course of activities.

Sec. 65B then lays down that for the purpose of evidence, a certificate identifying the electronic record containing the statement and describing the manner in which it is produced by a computer and satisfying the conditions mentioned above, and signed by an officer in charge of the operation or management of the related activities, shall be the evidence of any matter stated in the certificate; it shall be sufficient for a matter to be stated to the best of the knowledge and belief of the person stating it.

Rules as to Notice to Produce [Section 66]: Secondary evidence of the contents of the documents referred to in S. 65, clause (a), shall not be given unless the party proposing to give such secondary evidence has previously given to the party in whose possession or power the document is, or to his attorney or pleader, such notice to produce it as is prescribed by law; and if no notice is prescribed by law, then such notice as the Court considers reasonable under the circumstances of the case:

Provided that such notice shall not be required in order to render secondary evidence admissible in any of the following cases, or in any other case in which the Court thinks fit to dispense with it:

- When the document to be proved is itself a notice;

- When, from the nature of the case, the adverse party must know that he will be required to produce it;

- When it appears or is proved that the adverse party has obtained possession of the original by fraud or force;

- When the adverse party or his agent has the original in Court;

- When the adverse party or his agent has admitted the loss of the document;

- When the person in possession of the document is out of reach of, or not subject to, the process of the Court.

Sec. 66 lays down that a notice (to produce a document) must be given before secondary evidence can be received under Sec. 65 (a). The notice is to be given to the party who has possession of the original document, or to his attorney or pleader. Notice should be given in a manner as is prescribed by law, and if there is no law on the point, such notice should be given as the court considers reasonable under the circumstances of the case.

A question arises: when the opposite party fails to produce the original when demanded and the court has accordingly admitted secondary evidence, can the party in possession subsequently produce the original of his own choice ? The answer is “No”. Sec. 164 clearly lays down that where a party has required to another to produce a document and he has refused to do so, he can’t afterwards use the document as evidence unless he obtains the other party’s consent or the court’s order.

The requirement of notice under Sec. 66 is to be strictly complied with. The other party cannot be restrained from producing the original where the notice to produce has not been given, nor can secondary evidence be given in such case.

Section 67 (Proof of signature and handwriting of person alleged to have signed or written document produced)

“If a document is alleged to be signed or written by any person, the signature or the handwriting of so much of the document as is alleged to be in that person’s handwriting must be proved to be in his handwriting.”

Section 67A (Proof as to Digital Signature)

“Except in the case of a secure digital signature, if the digital signature of any subscriber is alleged to have been affixed to an electronic record the fact that such signature is the digital signature of the subscriber must be proved.”

Sec. 67 does not prescribe any particular mode of proof of signature or handwriting of a person. However, the following modes of proving a signature or writing are recognized by the Act, viz.

- by calling the person who signed or wrote the document;

- by calling a person in whose presence the document was signed or written;

- by calling a handwriting expert (Sec. 45);

- by calling a person acquainted with the handwriting of the person executing the document (Sec. 47);

- by comparing in court the disputed signature/ writing with some admitted signature/writing (Sec. 73);

- by proof of admission by the person who is alleged to have signed or written the document, that he signed or wrote it; or

- by statement of a deceased professional scribe, made in the ordinary course of business, that the signature on the document is that of a particular person.

- Any other circumstantial evidence.

Section 68 (Proof of Execution of Document Required by Law to be Attested)

To attest is ‘to bear witness to a fact. A document the execution of which is required by law to be “attested” means a document the signature upon which should be put in the presence of two witnesses who themselves add their signatures and addresses in proof of the fact that the document was signed or executed in their presence. They are called ‘attesting witnesses’.

Attestation does not imply that the attesting witnesses have admitted to the contents of a document. Section 68 lays down that if a document required by law to be attested is produced as evidence, at least one attesting witness shall be called to prove the execution of the document. This principle will apply only if at least one of the attesting witnesses is alive, capable of giving evidence and subject to the process of the court.

Section 68 further provides that no attesting witness need be called in the case of document (not being a will), which has been registered under the Indian Registration Act 1908 and the person executing it does not specifically deny its execution. If there is a denial, then , attesting witness have to be called.

Section 69 (Proof where No Attesting Witness Found)

“If no such attesting witness can be found, or if the document is executed in the United Kingdom, it must be proved that the attestation of one attesting witness at least is in his handwriting, and that the signature of the person executing the document is in the handwriting of that person.”

Section 70 (Admission of Execution by Party to Attested Document)

Sec. 70 lays down that ‘where the party to an attested document has admitted that he executed the document that is sufficient proof of the execution even if the document is required by law to be attested’. This admission’ relates only to the execution and to be made in the course of the trial of a suit or proceeding. It must be distinguished from the admission mentioned in Secs. 22 and 65 (b), which relate to the contents of a document.

The admission must be unqualified. Thus, if a person admits his signature on a mortgage-bond, but denies that the attesting witnesses were present at that time, the bond will have to be proved under Sec. 68, by calling the attesting witnesses.

Section 71 (Proof when Attesting Witness Denies the Execution)

Sec. 71 lays down that if the attesting witness denies or does not remember the execution of the document, its execution should be proved by other evidence’. Thus, the fate of an attested document does not lie at the mercy of an attesting witness; if he turns hostile, other evidence may be given; such a document may then be proved in the same manner as documents not required to be attested.

Sec. 71 is in the nature of a safeguard to the mandatory provisions of Sec. 68 to meet a situation where it is not possible to prove the execution of the will by calling the attesting witnesses, though alive. Sec. 71 is permissive and enabling section permitting a party to lead other evidence in certain circumstances.

Case Laws

Badri Narayanan v Rajabajyathammal (1996) 7 SCC 101

Where the attester was an illiterate person and he attested by putting his thumb impression, he was not bound by the document unless it could be shown that the document was read out to him and he understood it.

Section 72 (Proof of Document Not required by Law to be Attested)

“An attested document, not required by law to be attested, may be proved as if it was unattested.” To prove an attested document, one must prove attestation, and signature.

To prove an unattested document, one has to prove execution only.

Section 73 (Comparison of Signature, Handwriting, etc. by the Court)

According to Sec. 73, when the Court has to satisfy itself whether the signature, writing or seal on a document is genuinely that of a person whose signature, etc. it purports to be, the Court may compare the same with another signature, etc. which is admitted or proved to be that of the person concerned although that signature, etc. has not been produced or proved for any other purpose. This section applies also, with necessary. modifications, to finger impressions.

Sec. 73 also enables the court to require any person present in the Court to write any words or figures to enable the court to compare them with the words or figures alleged to have been written by such person (Power to ask for specimen handwriting).

Whether the Court should do the comparison itself or appoint an expert is a matter of discretion ?

In Murarilal v State of M.P. (AIR 1980 SC 531): It observed that the argument that the Court should not venture to compare writings itself, as it would thereby assume to itself the role of an expert is entirely without force. It is the plain duty of the court to compare the writings and come to its own conclusions. Where there are expert opinions, they will aid the court. Where there is none, the court will have to seek guidance from authoritative textbooks and the court’s own experience and knowledge.

Ajit Savant v State AIR 1997 SC 3255

However, the court should be slow in making self-comparison (particularly where the signature with which comparison is to be made is in itself not an admitted signature. The court can attempt a comparison, but in the case of slightest doubt, should rely upon the wisdom of experts The court cannot substitute its opinion for that of an expert. Weak expert opinion may be corroborated by the court’s opinion under the section.

Sec. 73 does not make any difference between civil and criminal proceedings. It is not limited to parties to the litigation. By virtue of the expression “any person” used in Sec. 73, the court can direct even a stranger to give a specimen of his handwriting.

State of Haryana v Jagbir Singh (2003) 11 SCC 261

It may be noted that where the case is still under investigation and no proceedings are pending before the court, a person present in the court cannot be compelled to give his specimen handwriting. The direction is to be given for the purpose of enabling the court to compare and not for the purpose of enabling the investigation or other agency “to compare”. In pendency of proceedings, it is sine qua non.

Sec. 73A (Proof as to Verification of Digital Signature)

“In order to ascertain whether a digital signature is that of the person by whom it purports to have been affixed, the court may direct-

- that person or the Controller or the Certifying Authority to produce the Digital Signature Certificate;

- any other person to apply the public key listed in such Certificate and verify the digital signature.”

The Explanation to this section states that for the purpose of this section “Controller” is same as mentioned in sub-sec. (1) of Sec. 17 of Information Technology Act, 2000.