BACKGROUND

Unlike Constitutional and other statutory laws, criminal law is not right-facilitating. It mostly penal or rarely remedial in nature. But self-help is the first rule of every remedial law. The right of private defence is absolutely necessary for the protection of one’s life, liberty and property—a right inherent in every person. But the kind and amount of force required/justified in repelling the force by another force is minutely regulated by law. Criminal law, although a law of penal standards which does not supplant rights like other law, assumes that every individual must stand his ground in the face of danger and not hesitate to defend his own body or property or that of another. He would respond with defensive force to prevent certain crimes, even to the extent of causing death. As a general idea, the right of private defence permits individuals to use defensive force which otherwise be illegal, to fend off attacks threatening certain important interests. Like the defence of necessity, the right of private defence authorises individuals to take the law into their own hands. However, the most important principle in this context is that the right of private defence requires that the force used in the defence should be necessary and reasonable in the circumstances. But, in the moments of disturbed mental condition, this cannot be measured in golden scales. Although law presumes that the force used in defence must either be proportionate to the force intended to be repelled or sufficient to repel it and avoid the apprehension thereof, it does not bind an individual exercising the right to weigh in golden scales the magnitude of force to be used. Specific limitations are also been provided for when the right cannot be validly exercised and also the provision specifies clearly the cases in which the right can extend to the causing of death of the aggressor. This right is based on two principles:

- It is available against the aggressor/assailant only, and

- The right is available only when the defender entertains reasonable apprehension of harm

Hence, the right of private defence serves a social purpose and needs to be guardedly resorted to, liberally construed and cautiously allowed to plead. Such a right is not only a coercive influence on corrupt characters but also encourages manly spirit in a law-abiding citizen. The need for its narrow construction (application to various cases) lies also in the fact that it necessitates the occasions for the exercise of this right as an effective means of protection against wrong doers. Therefore, it might have a pulverizing effect to the purpose of criminal thereby being susceptible to usage as an instrument of vengeance by unscrupulous people under the guise of law. Law, therefore, has devised three primary approaches (tests) to check and validate the claims of this defence—

- Objective: While objective test emphasizes as to how in a similar circumstance an ordinary, reasonable, standard and average person will respond

- Subjective – subjective test examines the mental state of each subject (individual) placed in the circumstances before the court in that case and based on individual attitude possessed by that person (educational, societal and mental background, ).

- Expanded objective tests– expanded objective test, being a combination of aforesaid two tests, bases its inquiry to ascertain and determine whether or not the individual acted as a reasonable person.

This right is, therefore, aptly described as a shield and not a sword as law does not equip an individual with it for the purpose of meeting his passions of vengeance or using it as a tool to resort to criminality.

PRIVATE DEFENCE IN THE INDIAN PENAL CODE, 1860.

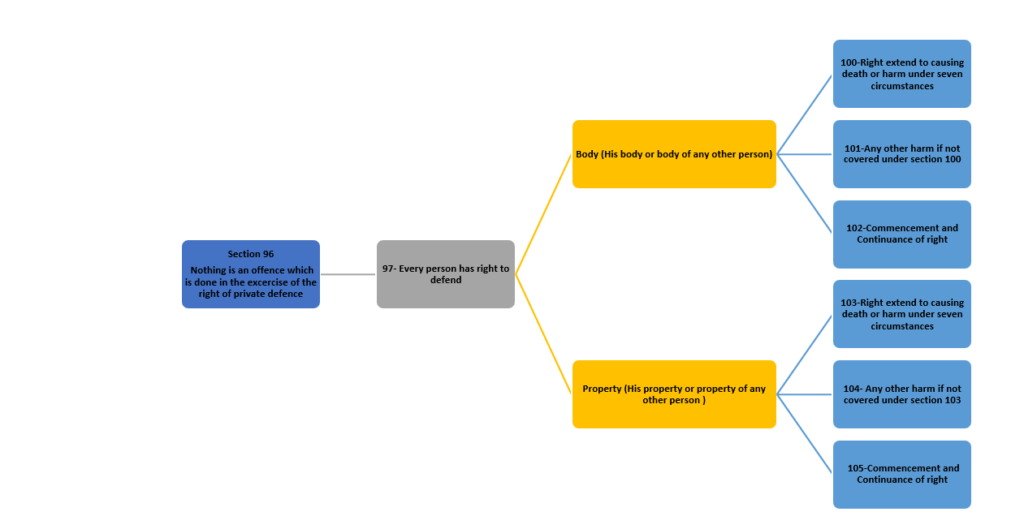

INTRO: The right of private defence has been recognized in the Indian Penal Code, 1860 under General Exceptions in the last 11 sections of Chapter IV starting with Section 96 and up to Section 106. Section 96 recognizes this right in a way too general sense while the remaining sections make provisions for varied forms of this right.

General Provisions regarding Private Defence:

Section 96 : Section 96 provides that nothing is an offence, which is done in the exercise of the right of private defence.

Right of private defence has been clearly incorporated in the Penal Code with a purposive scheme in mind and cannot be said to be an offence in return; rather it must proceed on the presence of a reasonable apprehension of harm to person or property. The reasonable apprehension can only be justified if the accused had an honest belief that there is danger and that such belief is reasonably warranted by the conduct of the aggressor and the surrounding circumstances. The right of self-defence under Section 96 is not exhaustive. It is actually extended by the succeeding provisions of the code (Section 97-106) with varying degrees of circumstances.

Section 97 : This section answers the two questions by delineating the nature and application of this right.

Right of Private Defence can be categorized as follows:

Answering the above questions, find that the section provides that a person can defend through the exercise of the right of private defence:

- His own body or body of any other person. As such he can defend any human body including his own against any offence affecting the human body (Chapter XVI of the Penal Code deals defines and penalizes offence affecting the human body).

- His own property or the property of any other person, whether movable or immovable, against any act which is either the commission or an attempt of an offence falling under the definition of any of the four offences listed below:

- Theft (378)

- Robbery (390)

- Mischief (425)

- Criminal Trespass (441)

All these offences are listed under Chapter XVII of the Penal Code under the head “Offences against Property” and the offences themselves serve as a threshold or head of species of offences which, naturally, get included in the definition of the offence itself listed in the second clause of section 97 by the usage of expression “any act which is an offence falling under the definition of”. As such, this right extends, not only to the cases of theft under section 378 but, also other forms of theft like theft in a dwelling house under section 380. Similarly, same applies to the rest of the offences listed above like Dacoity under Section 391, Dacoity with murder under Section 396, offences enumerated after the definition of Mischief under Section 425 i.e. offences from Section 426 to Section 440 and House-Trespass under Section 442, Lurking House-Trespass under Section 443, etc.

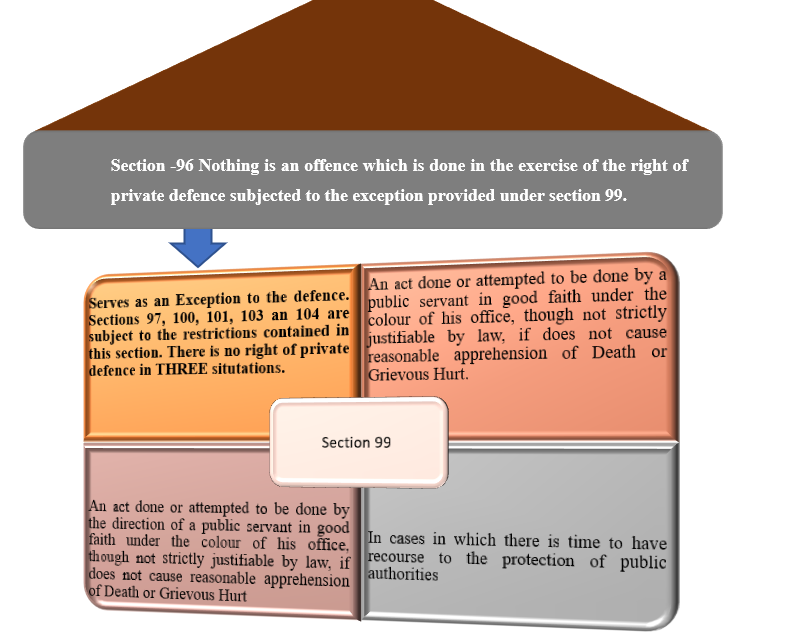

(This right of private defence is available subjected to the conditions provided in Section 99 Subject to the restrictions contained in section 99)

Sukumaran v/s State Rep. by the Inspector of Police[1]

The Supreme Court, in this case, acquitted the Tamil Nadu forest ranger who was accused of killing a sandalwood smuggler in a certain forest area by shooting him. The trial court had sentenced him to life imprisonment for murder. However, the Madras High Court reduced the term to five years. In appeal to the Apex Court, the accused contended that he had threat to his own life and that of his driver from the deceased smuggler. Acquitting the accused the Court observed, “The right embraces the protection of property, whether one’s own or another person’s, against offences like theft, robbery, mischief and criminal trespass…mere a reasonable apprehension is enough to put the right of self-defence into operation. In other words, it is not necessary that there should be actual commission of the offence in order to give rise to the right of private defence.” The appellant having seen the suspicious movements of the deceased party in the forest area rightly formed an opinion that the deceased party was moving around in the forest to smuggle the sandalwoods. Therefore, he was entitled to chase the deceased party and apprehend them for being prosecuted for commission of offence punishable under the forest laws. Indeed, that was his duty; also there was no motive attributed to the appellant towards any member of the deceased party.

Section 98: If the act is harmful in nature, but not an offence by reason of a mistake, infancy, insanity, intoxication, etc. the right shall still remain available in the same manner as if it were an offence.

Section 99 : There are some restrictions as envisaged in Munney Khan vs State [2]

Which says :

All sections (96-106) all read together to know the scope and limitation of this defence. The following limitations will apply to this defence :

- If there is a sufficient time for response to public authorities than no right of private defence

- There should be reasonable apprehension of hurt , grivious hurt or death to the person or damage to the property

- The force used and harm caused should be only as much as reasonably necessary

Public servant or act done by direction of public servant.

There is no right of private defence against an act which does not reasonably cause the apprehension of death or of grievous hurt, if done, or attempted to be done, by a public servant acting in good faith or by the direction of a public servant acting in good faith under color of his office, though that act may not be strictly justifiable by law.

Condition : The person should know that the act is done by a public servant or under his direction and should be shown the authority proof if demanded as provided in the explanation of the section.

Kesho Ram vs Delhi Administration[3]

The appellant was convicted u/s 353/332/333 of the Indian Penal Code and was sentenced accordingly. The prosecution case was that the appellant obstructed 3 inspectors and a peon of the Delhi Municipal Corporation, when they went to seize the appellants’ buffalo in the discharge of their duty to realize the milk tax from him and struck one of the officers on the nose with the result that it bled and was found fractured. The main contention of the appellant was that the attempt to realise the arrears of milk tax and recovery charges was illegal because no demand noticed under Sec. 154 of the Act was served on the appellant, and therefore, he had the right of private defence. The prosecution relied on Sec. 99 Indian Penal Code which provides that there is no right of private defence against an act of a public servant, done in good faith under colour of his office, though that act may not be strictly justifiable by law. Further according to the prosecution, Sec. 161 of the Act empowered the Inspector of the Corporation to seize and remove the appellant’s buffalo for non-payment of tax and the section gave them an over-riding power to resort to seize and detention of the animal. Therefore, according to the prosecution, the appellant was guilty of the offences charged. The Court held that an immunity under Section 99 of the IPC can be claimed by a public servant, if he acted in good faith under the colour of his office even though the legality of the act could not otherwise be sustained.

In the case of Ritaram Besra vs State of Bihar[4] the right of private defence does not extend to inflicting of more harm than necessary for the purpose of defence. The prosecution party, in this case, had gone to plough the land which was in the possession of the accused (appellant). The latter had time to go and report the matter to appropriate authorities constituted under the law. But instead of so doing, they brutally attacked the other party resulting in the death of three persons. Thus, there was no right of private defence. It was held that there was no warrant for converting the conviction from u/ s. 302 to s. 304 Part II.

Private Defence against Body

Section 100: This section covers the right of private defence of body, which means a human body. Section 100 recognizes this right in the seven most brutal form of acts to the extent of even causing death of the assailant but subject to the restrictions contained under Section 99. These are :

- First. -Assault with apprehension of death.

- Secondly. -Assault with apprehension of grievous hurt;

- Thirdly. -An assault with the intention of committing rape;

- Fourthly. -An assault with the intention of gratifying unnatural lust;

- Fifthly. -An assault with the intention of kidnapping or abducting;

- Sixthly. -An assault with the intention of wrongfully confining a person, under circumstances which may reasonably cause him to apprehend that he will be unable to have recourse to the public authorities for his release.

- Seventhly: An act of throwing or administering acid or an attempt to throw or administer acid which may reasonably cause the apprehension that grievous hurt will otherwise be the consequence of that act.[5]

In the case of Mohinder Pal Jolly v. State of Punjab[6] Workers of a factory threw brickbats from outside the gates, and the factory owner by a shot from his revolver caused the death of a worker, it was held that this section did not protect him, as there was no apprehension of death or grievous hurt.

In the case of Bhadar Ram vs State of Rajasthan the accused heard the cries for help of his widowed sister in law. He ran to her house with gandasa. He found the attacker grappling with her and trying to outrage her modesty. The accused saved her from his clutches and inflicted a gandasa blow while he was going to run away. The act of the accused was held to have been done in the right of private defence.[7] The accused was acquitted.”

Section 101: If the offence is not of any of the descriptions listed above, this right extends to the extent of causing any harm to the assailant other than death.

Section 102: Commencement and Continuance of Right of Private Defence.

The right commences as soon as a reasonable apprehension of danger to the body arises from an attempt or threat to commit the offence though the offence may not have been actually committed; and it continues as long as such apprehension of danger to the body continues. The apprehension of danger must be reasonable, not fanciful.

For example, one cannot shoot one’s enemy from a long distance, even if he is armed with a dangerous weapon and means to kill because the danger must be present and imminent, proximate, real and based on substance.

Section 103-105: Private Defence of Property

This part follows the similar scheme as discussed above.

Section 103: When you can Cause Death while exercising Private defence of Property. These conditions are:

- First. -Robbery;

- Secondly. -House-breaking by night;

- Thirdly. -Mischief by fire committed on any building, tent or vessel, which building, tent or vessel is used as a human dwelling, or as a place for the custody of property;

- Fourthly. -Theft, mischief, or house-trespass, under such circumstances as may reasonably cause apprehension that death or grievous hurt will be the consequence, if such right of private defence is not exercised.

In the case of James Martin vs State of Kerala[8] the accused did not close his flour mill on the day of “Bharat Bandh” organized by some political parties. The activists entered the mill and demanded closure. They were armed with sharp-edged weapons. They threatened and assaulted the person who was operating the mill. He fired at them resulting in death of two persons and also injuring some innocent people. His property was set on fire. It was held that the acts of the accused were within the reasonable limits of the right of private defence. His conviction was set aside.

Section 104 – Any other harm than death for offences not falling under Section 103 and restrictions of (Section 99.

Section 105 – Commencement and Continuance of the right of Private Defence: This delineating the contours of this right—commencement and continuance.

The Right of private defence of property with respect to all the offences against property (mentioned either in section 97 or section 103) i.e. theft, robbery, mischief, criminal trespass and house–breaking by night commences when a reasonable apprehension of danger to the property commences. Regarding the continuance of the right, this section specifies separate time points of time.

- In theft, it continues till the offender has affected his retreat with the property or either the assistance of the public authorities is obtained, or the property has been recovered.

- In robbery, the right continues as long as the offender causes or attempts to cause to any person death or hurt or wrongful restraint or as long as the fear of instant death or of instant hurt or of instant personal restraint continues.

- In criminal trespass or mischief, it continues as long as the offender continues in the commission of criminal trespass or mischief.

- In house-breaking by night continues as long as the house-trespass which has been begun by such house-breaking continues.

Section 106:

Section 106 lays down the provision for the right of private defence against a deadly assault when this right cannot be exercised without running the risk of harm to innocent person. If in the exercise of this right, whether in case of body or property, against an assault which reasonably causes the apprehension of death, the defender be so situated that he cannot effectually exercise that right without risk of harm to an innocent person his right or private defence extends to the running of that risk.

Illustration: A is attacked by mob who attempt to murder him. He cannot effectually exercise his right of private defence without firing on the mob, and cannot fire without risk of harming young children who are mingled with the mob. A commits no offence id by so firing , he harms any of the children.

Burden of Proof: It is pertinent to tell you here that if the right of private defence is claimed by an accused as a lawful excuse for his act, the burden of proof rests upon him. Section 96, Penal Code is one of the general exceptions and lays down that nothing is an offence which is done in the exercise of the right of private defence. You must remember that when a person is accused of any offence the burden of proving the existence of circumstances bringing the case within any of the general exceptions in the Indian Penal Code is upon him and the Court shall presume the absence of such circumstances (section 105 Evidence Act read and explained). It follows therefore that an accused is not entitled to the benefit of any exception such as that provided for in Section 98, Penal Code merely because there is a reasonable doubt in the mind of the Court about the existence of circumstances bringing the case within the exception.”

It is a well-settled principle that the accused need not prove their case beyond all reasonable doubt in a plea of self-defense under Section 105 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. On account of preponderance of probabilities, if the plea of self-defense becomes plausible, then the same should be accepted or at least, a benefit of doubt arises.

The Supreme Court, in Salim Zia vs State of UP [9]made a landmark point that the accused might not take this plea explicitly or adduce any evidence in support of it but he can still succeed in getting the plea of private defense if he is able to bring out materials on record, on the basis of evidence of the prosecution witnesses or on other pieces of evidence, to show that the criminal act which he committed was justified in exercise of his right of private defense of person or property, or both. If the plea of right of private defense put forward by the accused appears to be quite probable, it cannot be rejected.

In GVS Suvrayanam vs State of AP[10] the Supreme Court held that the court is not precluded from giving to the accused the benefit of the right of private defense even where the plea of self-defense was not raised by him, if on proper appraisal of the evidence and other relevant material on the record, the court concludes that the circumstances in which he found himself at the relevant time gave him the right to use his gun in exercise of this right.

Conclusion

The right of private defence has been recognised in law in almost all the countries today. It is a right of a person to defend body and property of himself and others. If someone commits an act in this process, it is no offence. Subject to limitations and conditions, it a right of every individual. The law has given liberty to a person in lieu of private defence to even cause death in certain cases. This is because the law has itself has accepted that self protection is the primary duty of every individual. Law will not be able to help someone who is not capable of helping himself when something wrong happens to that person.