The key word is “Review which used as noun, means looking over something again; judging again; reconsideration; reassessment; critical examination.

Broadly speaking, judicial review in India deals with these aspects:

- Judicial Review of Legislative Actions

- Judicial Review of Constitutional Amendments

- Judicial Review of Administrative Actions

Here we are concerned with judicial review of administrative actions.

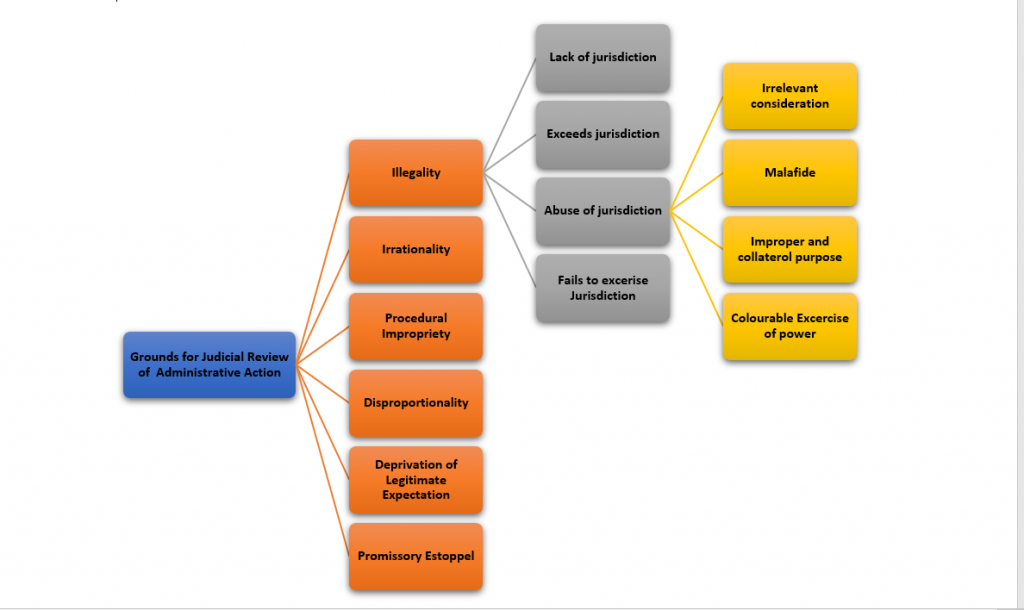

Grounds for the Exercise of the power of Judicial Review of Administrative Action:

- Illegality;

- Irrationality;

- Procedural Impropriety;

- Disproportionality;

- Deprivation of Legitimate Expectation.

Though these grounds of judicial review are not exhaustive, yet these provide an apt base for the courts to exercise their jurisdiction.

- Illegality

This ground of judicial review is based on the principle that administrative authorities must correctly understand the law and its Limits before any action is taken. Therefore, if the authority

- lacks jurisdiction, or

- exceeds jurisdiction, or

- abuses jurisdiction, or

- fails to exercise jurisdiction

It shall be deemed that the authority has acted “illegally”. Court may quash an administrative action on the ground of illegality in following situations.

- Lack of Jurisdiction

Case Laws :

State of Gujrat vs Patel Raghav Nath 1969

The revision also authority exercising powers under the land revenue code went into the question of title.The Supreme Court observed that when the title of the occupant was in dispute the appropriate course would be to direct the parties to approach the civil court and not to decide the question.

In R v. misnomer of Transport 1934 : Even though minister had no power to revoke licence , he passed an order of revocation. The action was held ultra vires and without jurisdiction.

- Exceeding Jurisdiction

An administrative authority must exercise the power within the limits of the statute and if it exceeds those limits, the action will be held ultra

vires.

For example, if an officer is empowered to grant a loan of Rs. 1,00,000 in his discretion for a particular purpose and if he grants a loan of Rs.2,00,000, he exceeds his power (jurisdiction) and the entire order is ultra vires and void on that ground.

GES Corporation v. Workers Union (1959) :The authority is empowered to award a claim for the medical aid of the employees. The authority granted the said benefit to the family members of the employees. Held that the authority exceeded his powers.

- Abuse of jurisdiction

All administrative powers must be exercised fairly, in good faith, for the purpose it is given, therefore, if powers are abused it will be a ground for judicial review

Abuse of jurisdiction may be inferred from the following circumstances:

- Irrelevant considerations;

- Mala fide;

- Improper purpose: Collateral purpose;

- Colourable exercise of power;

- Irrelevant considerations

A power conferred on an administrative authority by a statute must be exercised on the considerations relevant to the purpose for which it is conferred. Instead, if the authority takes into account wholly irrelevant or extraneous considerations the exercise of power by the authority will be ultra vires and the action bad.

Hukam Chand v. Union of India (1976) : In this case , under the relevant rule, the Divisional Engineer was empowered to disconnect any telephone on the occurrence of a ‘public emergency’. When the petitioner’s telephone was disconnected on the allegation that it was used for illegal forward trading (satta) the Supreme Court held that it was an extraneous consideration and arbitrary exercise of power by the authority.

- Mala fide

If the power is not exercised bona fide, the exercise of power is bad and the action illegal. Though precise and scientific definition of the expression “mala fide” is not possible, it means ill will, dishonest intention or corrupt motive.

In Rowjee v. State of A.P 1964., the State Road Transport Corporation had framed a scheme for nationalisation of certain transport routes. This was done as per the directions of the then Chief Minister. It was alleged by the petitioner that particular routes were selected to take vengeance against the private transport operators of that area as they were the political opponents of the Chief Minister. The Supreme Court upheld the contention and quashed the order.

- Improper object: Collateral purpose

In Nalini Mohan v. District Magistrate (1951), the relevant statute empowered the authority to rehabilitate the persons displaced from Pakistan as a result of communal violence. That power was exercised to accommodate a person who had come from Pakistan on medical leave. The order was set aside.

- Colourable exercise of power

Where a power is exercised by the authority ostensibly for the purpose for which it was conferred, but in reality for some other purpose, it is called colourable exercise of power. Here, though the statute does not empower the authority to exercise the power in a particular manner, the authority exercises the power under the ‘colour’ or guise of legality.

“WHAT CANNOT BE DONE DIRECTLY CANNOT ALSO BE DONE INDIRECTLY”

In Vora v. State of Maharashtra (1984) : In this case , the State Government requisitioned the flat of the petitioner, but in spite of repeated requests of the petitioner, it was not derequisitioned. Declaring the action bad the court observed that though the act of requisition was of a transitory character, the Government in substance wanted the flat for permanent use, which would be a ‘fraud upon the statute’.

- Failure to Exercise Jurisdiction

If any administrative authority has been given power by law, no matter discretionary, the authority must exercise it in one way or the other. Public power is not a personal power, it is a public trust and, therefore, must be exercised in public interest. Failure or denial to exercise jurisdiction will be an illegality. Such type of flaw may arise in the following circumstances:

- Sub-delegation;

- Imposing fetters on discretion by self-imposed rules of policy;

- Acting under dictation;

- Non-application of mind

Case Laws :

In the case of Commissioner of Police v. Gordhandas (1952), under the City of Bombay Police Act, 1902 the Commissioner of Police was authorised to grant licenses for construction of cinema theatres. The Commissioner granted licence for the construction of a cinema theatre. But later on, he cancelled it at the direction of the State Government. The Supreme Court set aside the order of cancellation of licence.

Mansukhlal v. State of Gujarat (1997) :In that case, the government did not grant sanction to prosecute appellant (public servant) under the Prevention of Corruption Act. The complainant filed a petition in the High Court and the High Court ‘directed’ the authorities to grant sanction. The appellant was prosecuted and convicted. Setting aside the conviction, the Supreme Court observed that “by issuing a direction to the Secretary to grant sanction, the High Court closed all other alternatives to the Secretary and compelled him to proceed only in one direction”. The sanction was, therefore, illegal and conviction bad in law.

- Irrationality (Wednesbury Test)

A general established principle is that the discretionary power conferred on an administrative authority should be exercised reasonably. A decision of an administrative authority can be held to be unreasonable if it is so outrageous in its defiance of logic or prevalent moral standards.

Associated Provincial Picture Houses vs. Wednesbury Corporation [1948]:”Associated Provincial Picture Houses” were granted a licence by the defendant local authority to operate (SCREEN A MOVIE)a cinema on condition that no children under 15 were admitted to the cinema on Sundays. The claimants sought a declaration that such a condition was unacceptable, and outside the power of the Wednesbury Corporation to impose.

THE WEDNESBURY PRINCIPLE

A decision will be said to be unreasonable in the Wednesbury sense if

- it is based on wholly irrelevant material or wholly irrelevant consideration,

- it has ignored a very relevant material which it should have taken into consideration, or

- it is so absurd that no sensible person could ever have reached to it. (If it is so outrageous in its defiance to logic or accepted norms of moral standard that no sensible person, on the given facts and circumstances, could arrive at such a decision.

- Procedural impropriety

If a statute lays down any procedure which administrative authority must follow before taking action, it must be faithfully be followed and any violation of the procedural norm would vitiate an administrative action.

Where statute is silent about the procedure, courts have insisted that the administrative authorities must follow the principles of natural justice while taking a decision which has civil or evil consequences ( has impact on any individual).

Therefore, principles of natural justice need to be followed with respect to an administrative action when the action is likely to have an impact on any individual.

- Doctrine of Proportionality

The doctrine of proportionality is emerging as a new ground of challenge for judicial review of administrative discretion. It is a recognised general principle of law evolved with a purpose to maintain a proper balance between any adverse effects which its decision may have on the rights, liberties or interests of persons and the purpose it pursues. The doctrine of proportionally endeavours to confine the exercise of discretionary powers of administrative authority to mean which are proportioned to the object to be pursued.

The courts while invoking the doctrine of proportionality may quash the exercise of powers in which there is not a responsible relationship between the objective which is sought to be achieved and the means used to that end.

In the case of Union of India vs Kuldeep Singh 2004 The Supreme Court while invoking the principle of Proportionality has held that penalty imposed must be in proportionate with the gravity of misconduct if any penalty disproportionate of misconduct would be violative of Article 14 of the Constitution.

In Ranjit Thakur v. Union of India(1987) – an army officer did not obey the lawful command of his superior officer by not eating food offered to him. Court martial proceedings were initiated and a sentence of rigorous imprisonment of one year was imposed. He was also dismissed from service, with added disqualification that he would be unfit for future employment. The said order was challenged.

The said order was set aside on the ground that the punishment was grossly disproportionate.

- Doctrine of Legitimate Action

The doctrine of legitimate expectation belongs to the domain of public law. It is proposed to give relief to the people when they are not able to justify their claims on the basis of law. As they had suffered a civil consequence because their legitimate expectation had been violated.

Lord Denning first used the term legitimate expectation’ in 1969 and from that time it has assumed the position of a significant doctrine of public law in almost all jurisdiction. In India, this doctrine had been developed by the court in order to check the arbitrary exercise of power by the administrative authorities. According to private law a person can approach the court only when his right based on statute or contract is violated, but this rule of locus stand is relaxed in public law to allow standing even when a legitimate expectation from a public authority is not fulfilled. This doctrine grants a central space between ‘no claim’ and a ‘legal claim’ wherein a public authority can be made accountable on the ground of an expectation, which is legitimate.

For example, if the Government has made a scheme for providing drinking water in villages in certain area but later on changed it so as to exclude certain village from the purview of the scheme then in such a case what is violated is the legitimate expectation of the people in the excluded villages for tap water and the government can be held responsible if exclusion is not fair and reasonable. Thus, this doctrine becomes a part of the principles of natural justice and no one can be deprived of this legitimate expectation without following the principles of natural justice.

SC of WS Welfare Association vs. State of Karnataka (1991):

In this case the Government has issued a notification notifying areas where slum clearance scheme will be introduced. However, the notification was subsequently amended and certain areas notified earlier was left out. The Court held that the earlier notification had raised legitimate expectation in the people living in an area which had been left out in a subsequent notification and hence legitimate expectations cannot be denied without a fair hearing.

________________________________________________________________