Introduction:

An admission is a statement of fact which waves or dispenses with the production of evidence by conceding that the fact asserted by the opponent is true. It is a voluntary acknowledgement made by the party or somebody identified with him in legal interest. The Supreme Court observed that admissions are very weak kind of evidence and the court may reject them if it is not satisfied from other circumstances that they are untrue.

Admission literally means acknowledgment of a fact. S. 17 defines it as statement, oral or documentary, suggesting an inference as to any fact in issue or relevant fact made by any of parties and under circumstances stated Us 18 to 20.

In CBI v. V. C. Shukla case, on 2nd March, 1998 distinguishing between admission and confession the Supreme Court observed: “Only voluntary and direct acknowledgement of guilt is a confession, but, if it falls short of actual admission of guilt, it may be used as evidence against the person who made it or his authorized agent, as an admission under section 21.

Section 17 of Indian Evidence Act:

According to Section 17 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 an admission is a statement, oral or documentary or contained in electronic form, which suggests any inference as to any fact in issue or relevant fact, and which is made by any of the persons, and under the circumstances, hereinafter mentioned.

Section 17 IEA defines “Admissions” but it is not complete definition. It is complete when it is read with other provisions of the Chapter especially Ss. 18 to 20.

Essential Ingredients of Admission:

- is a statement, oral or documentary or contained in electronic form;

- is a statement which suggests any inference as to any fact in issue or relevant fact;

- must be made any of the persons mentioned in the Act (Ss. 18 to 20);

- is made by any person under the circumstances have been mentioned in the Act;

- must be taken as a whole;

- The law of Admissions is exceptions to the law of hearsay; and

- Admissions of facts only bind persons making them.

Example:

A, files a suit against B alleging that B is the last male owner’s daughter’s son and that he (A) is the last male owner’s sapinda. B files a document in which A admits that B to be the daughter’s son of the last male holder. That document is the admission made by the A.

Kinds of Admissions:

There as two types of admissions:-

- Judicial, and

- Extra-judicial Admissions.

Judicial Admission:

The judicial or formal admission is addressed to the court and is the part of the proceeding. It is made on the record in the file of the court. The judicial admission may be made by the party in his pleading, or by stipulation, or by statement in open court.

In Bishwanath Prasad v Dwarka Prasad, AIR 1974 SC 117 case, the Supreme Court opined that “admissions, if true and clear, are by far the best proof of the fact admitted.” Admissions as defined in Sections 17 and 20 and fulfilling requirements of Section 21 are substantive evidence, propio vigare (of or by its own force independently).

Extra-judicial Admission:

The extra-judicial or informal admission is statement of fact made by the party previously in course of life or business which is inconsistent with the facts to be established at the trial. The extrajudicial admissions are called evidential admissions. The Evidence Act only deals with this sort of admission in Sections 17 to 23.

In Bessela v Stern, (1877), L. R. 2 C. P. D. 265 case, where the girl said to the boy “you always promised to marry me and you did not keep your words.” The boy did not deny the allegation, but he offered her some money. The boy’s silence as to promise was held to be admission.

Relevancy of Admission:

According to Section 3 of the Indian evidence Act, one fact is said to be relevant to another when the one is connected with the other in any of the ways referred to in the provisions (sections 5 to 55) of this Act relating to the relevancy of facts. ” The admission is relevant on the following reasons:

- Admissions as waiver of proof:

If a party has admitted a fact, it dispenses with the necessity of proving the fact against him. It operates as a waiver of proof. An admission, as an admission is not conclusive against the person making it, but it may operate as an estoppel under section 115 of the Evidence Act. Under the proviso to Section 58 the court may ask some other independent evidence to support the admitted facts. The court is not bound to give judgment in accordance with admission.

In Queen Empress v. Tribhovandas Manekchand, (1885) ILR 9 Bom 131case, the Court held that a confession which is inadmissible in a criminal proceeding may be used as an admission in a civil proceeding.

- Admissions as statement against interest:

It is natural for a man to make statement in his favour. An admission, being a statement against the interest of the maker should be supposed to be true, for it is highly improbable that a person will voluntarily make false statement against his own interest.

- Admissions as evidence of contradictory statements:

Where there is contraction between the statements of the party and his case, the contradiction is relevant. For example, A sues B upon a loan. The account book shows that the loan was given to C. The statement in his Account Book contradicts his case against B.

- Admissions as evidence of truth:

The statements made by the party about the facts of the case, whether they may go in his favour or against his interest, should be relevant as representation or reflecting the truth as against him. Whatever a party says in evidence against himself may be presumed to be so.

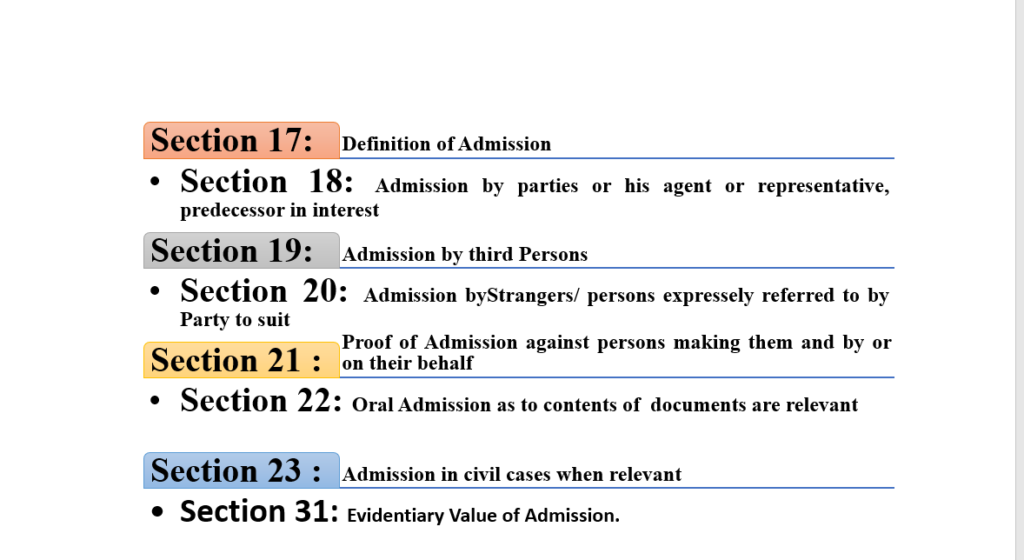

Provisions of Admission in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

The general principles concerning admission has been dealt with in following Sections:

_____________________________________________________________________

Persons Whose Admissions are Relevant (Secs. 18-20)

Secs. 18, 19 and 20 makes the statements of the following persons relevant:-

- A party to the suit or proceeding, an agent authorised by such party,

- A party suing or sued in a representative character making admissions while holding such character (e.g. trustees, executors, etc.),

- A person who has a proprietary/ pecuniary interest in the subject-matter of suit during the continuance of such interest,

- A person from whom the parties to suit have derived their interest in the subject-matter of suit during the continuance of such interest (predecessors-in-title) [Sec. 18];

- A person whose position it is necessary to prove in a suit, if such statement would be relevant in a suit brought by or against himself (Sec. 19);

- A person to whom a party to suit has expressly referred for information in reference to a matter in dispute (Sec. 20).

It is important to note that under Sec. 18, an admission by one of several defendants in a suit is no evidence against another defendant, for otherwise the plaintiff can defeat the case of the other defendants through the mouth of one of them. So a defendant is bound by his statements only to the extent of his own interest. So is true of the statement of a co-plaintiff. But since every plaintiff has a pecuniary interest in the subject-matter of suit, his statement can fall in that category.

In order to bind admission made by an agent, the following two conditions must be satisfied:

- Admission must have been made during the continuance of that relation;

- Admission must be made within the extent of his power and authority.

Thus, the acknowledgment of a debt by a partner is an admission against the firm. Likewise, admissions of facts made by a pleader in court, on behalf of his client, are binding on the client. But, an admission by a pleader on a point of law will not bind the client.

Third Party Admission:

Sec. 19 deals with statements of persons whose position is in issue, though they are not parties to the case. The section is based on the principle that where the right or liability of a party to a suit depends upon the liability of a third person, any statement by that third person about his liability is an admission against the parties.

Section 19 enacts an exception to the general rule that admission by stranger or third party are not binding. However, if conditions stated Us 19 are satisfied, then third party admission are also relevant. In order to attract S. 19, the following conditions must be satisfied:

- There must exist some relationship between the parties;

- The position or liability of a third party must be in existence and in issue between parties to the proceedings.

- Any admission made by such a person concerning his position or liability would be binding on the parties provided admission was made during the existence of that relationship.

Illustration to Sec. 19 – A undertakes to collect rents for B. B sues A for not collecting rent due from C to B. A denies that rent was due from C to B. A statement by C that he owed B rent is an admission, and is relevant fact against A, if A denies that C did owe rent to B.

Admission by Strangers / Referral Admission:

Section 20 enacts second exception to the general rule made under section 18 and states that admission by referees i.e. strangers are admissible. It is a tripartite arrangement as there are three parties i.e. one who refers; one who is referred; one to whom reference is made. The provision would be attracted where a party to a suit has expressly referred the matter to referee or stranger for making a statement irrespective of the fact that referee has any specific or particular knowledge regarding the subject matter. These are relevant but not conclusive unless they fall within the rule of estoppel under section 115 of Evidence Act.

To attract the operation of Section 20 , there must be an express reference for information in order to make the statement of the person referred to admissible.

Illustration:

The question is, whether a horse sold by A to B is sound.

A says to B – “Go and ask C, C knows all about it.” C’s statement is an admission

Against Whom Admission may be Proved

First part of Sec. 21 – “Admissions are relevant and may be proved as against the person who makes them, or his representatives in interest”

Sec. 21 lays down the principle as to proof of admissions. The section is based upon the principle that an admission is evidence against the party who had made the admission and, therefore, it can be proved against him.

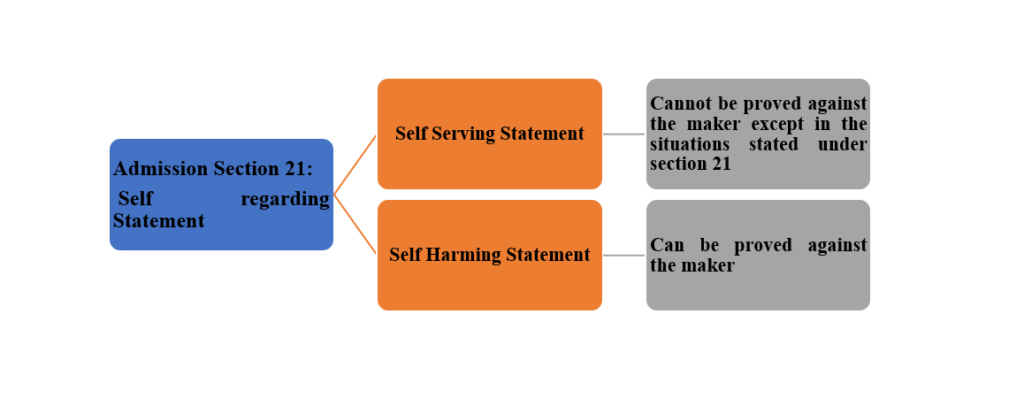

Any self-serving statement made under this section would be considered irrelevant unless it falls under the ambit of general exception as provided in second part of this section.

In R. v Petcherini (1855) 7 Cox. C.C.70: A spriest, facing the charge of blasphemy, was not permitted to prove his earlier statement to the effect that only immoral books should be destroyed.

Exception to Section 21:

A statement is in self-serving form when it is in favour of person making it and in self-harming form when it is against the interest of the maker.

For instance; A states that he is the owner of the property or that B owes him Rs. 2000/- are self-serving statement. A states that he is not the owner of this property or that A owes towards B Rs.2000/- are self-harming statement.

The general rule of relevancy with respect to such statement is that a statement in self-harming form is admissible but statement in self-serving form is not admissible. The reason for this rule is obvious; there can be no guarantee of truth of statement which is made to serve one’s own interest.

The Evidence Act reproduces the aforesaid principle in section 21 of the Act. It stipulates that an admission is relevant and can be proved against his maker or his representative-in-interest except in the three situations laid down below :-

- When a statement is made to a third person by a person who is no more alive. It would be relevant as between third persons under Sec. 32.

A statement/ admission which would be relevant as dying declaration or as that of a deceased person,

- Can also be proved by the maker himself if he is still

- Irrespective of whether it operates in favor of or against the person making the

Illustrations :

- A is accused of a crime committed by him at He claims being at Lahore at relevant time. A produces a letter written by himself and dated at Lahore on that day, and bearing the Lahore post-mark of that day.Here, the statement in the date of the letter is admissible, because, if A were dead, it would be admissible under Section 32(2).

- Immediately after a road accident, if the victim has made a statement to the rescuer about the cause of the accident he can prove that statement even after surviving the accident, because it is part of the same

- The captain of a ship is sued by the ship-owner for casting away the ship by his negligence. The ship-owner gave evidence of the fact that the ship was taken out of her course. The captain was maintaining a diary in the ordinary course of his duty in which he recorded the course that the ship followed and which showed that the ship was not taken out of her due course. Now, if the litigation was between the shipowner and the insurance company and the question was whether the ship was lost due to negligence or otherwise and the captain was dead, the contents of his book would have been relevant though they operate in his favour.

- The state of a man’s mind and body is relevant under section 14 of the Act and statements narrating such facts indication the state of mind or body may be proved on behalf of a person narrating them.

Exception 2 : Sec-21(2) read with Sec-14, Statements as to bodily feeling or mind –A person is allowed to prove his statement about his state of mind or body,- IF such state of mind or body is a fact in issue or is relevant fact

- AND if the statement was made at the time when such state of mind or body existed

- AND further if the statement is accompanied with his conduct that makes the falsehood of the statements.

Illustration:

If the question is whether a person has been guilty of cruelty towards his wife, he may prove his statements made shortly before or after the alleged cruelty, which explain his love and affection for and his feeling towards his wife.

Illustration:

Where the question is whether a person received a stolen property with knowledge that it was stolen. In order to prove that he did not have guilty knowledge, he offers to prove that he refused to sell the property below its value or natural price. His statement explains the state of his mind and is accompanied by the conduct of the refusal to sell. He may thus prove his statement.

Similarly, where a person is charged with having in possession a counterfeit coin with knowledge that it was counterfeit. He offers to prove that he consulted a skilful person on the matter and he was advised that the coin was genuine. He may prove this fact.

- Facts which are relevant under section 6 to 13 cannot be rendered inadmissible simply because they can be proved on behalf of the persons making them. Certain other relevant statements can also be proved by the party making it, such as, when the statement is itself a fact in issue or if it is a part of res gestae

The last exception allows a person to prove his own statement when it is otherwise relevant under any of the provisions relating to relevancy. There are many cases in which a statement is relevant

- Not because it is an admission

- But because it establishes the existence or non-existence of a relevant

In all such cases a party can prove his own statements.

For example, where plaintiffs sought to establish their pedigree by proving that A and B were brothers, a statement to that effect made by one of the plaintiffs long before the controversy arose, were held relevant. The statement admissible under clause (3) is also relevant under sections 6 to 13 and 34 and 35 of the Evidence Act. The statement of A in a previous proceeding that B was a tenant of the property in dispute is an admission and can be used when in the later proceeding he denied that fact.

Where, for example, immediately after a road accident, a person pulled up to the injured who then made a statement as to the cause of the injury. This statement may be proved by or on behalf of the injured person, it being a part of the transaction which injured him (Sec. 6).

Illustration: Where A says to B, “You have not paid back my money, and B walks away in silence, A may prove his own statement as it has influenced the conduct of a person whose conduct is relevant (Sec. 8).

Illustration: Where a person is seen running down a street in an injured condition and crying out the name of his assailant, he may prove his own statement as it accompanies some conduct and explains the fact of injury.

Case Laws :

Satrucharla Vijaya Ram Raju v Nimmaka Jaya Raju (2006) 1 SCC 212:

Where a person’s self-serving statement subsequently becomes adverse to his interest, it may be proved against him as an admission. “Though in a prior statement, an assertion in one’s own interest may not be evidence, a prior statement adverse to one’s interest would be evidence. Indeed, it would be the best evidence”.

Venugopal vs. A. Karrupusami (2006) 4 SCC 567:

Thus, stray statements in the deposition of the landlord showing that there was no personal need of the premises, amounted to an admission against his own interest in filing the eviction proceedings.

Delhi Transport Corporation v Shyam Lal AIR 2004 SC 4271

The admission of a bus conductor that he had taken money from a passenger without issuing ticket to him was considered to be the best piece of evidence against him. But he has a right to rebut it.

Chetan Constructions Ltd. vs. Om Prakash AIR 2003 A.P. 145:

Fact of the case was, the vendor of property admitted in his agreement, affidavits and other papers that delivery of possession was made to the purchaser on the date of the agreement, and subsequently he wanted to resile from admission saying that possession was only for sake of paper work, the court said that a heavy burden of proof would lie upon him to show that the statement was not true. The fact that a heavy amount was received for handing over immediate possession was strong evidence of delivery of possession and was not easy to be countered.

Admissions How Far Relevant (Secs. 22-23)

When oral admissions as to contents of documents are relevant (Sec. 22)

Oral admissions as to the contents of a document are not relevant, unless and until the party proposing to prove them shows that he is entitled to give secondary evidence of the contents of such document under Sec. 65, or unless the genuineness of the document produced is in question.

When the question is whether a document is genuine or forged, oral admissions about this fact are relevant. A document can be proved by the primary evidence (original document) or secondary evidence (attested copies or oral account).

Section 22 makes relevant oral admission regarding contents of document in the following two situations:-

- The oral admission is relevant and admissible as secondary evidence Us 63(5) i.e. oral account of contents of document given by a person who has himself seen it (i.e. original document).

- Where validity of document is itself under challenge i.e. Proviso to S. 92 of Indian Evidence Act.

When oral admissions as to contents of electronic records are relevant (Sec. 22A)

“Oral admissions as to the contents of electronic records are not relevant unless the genuineness of the electronic record produced is in question.

Admission in civil cases when relevant / Communication without prejudice (Sec. 23)

“In civil cases, no admission, is relevant, if it is made either upon an express condition that evidence of it is not to be given, or under circumstances from which the court can infer that the parties agreed together that evidence of it should not be given”.

Explanation – Nothing in this section shall be taken to exempt any barrister, pleader or attorney from giving in evidence of any matter of which he may be compelled to give evidence under Sec. 126. Sec. 23 gives effect to the maxim interest rei publicae ut finis litium (it is in the interest of the State that there should be an end of litigation).

Sec. 23 applies only to civil cases. When a person makes an admission “without prejudice”, i.e., upon the condition that the evidence of it shall not be given, it cannot be proved against him. This protection or privilege against disclosure is intended to encourage parties to settle their differences amicably and to avoid litigation if possible.

This section protects admissions or communications made without prejudice. It is applicable to civil cases. These are excluded on the ground of public policy. These may be made expressly or impliedly. In disputes parties generally exchange communication in order to settle the matter or buy peace but these are made with understanding that those would not be used in the court against them should the parties fail to settle the matter. Negotiations for compromise and statements made in the court during the process of making efforts for compromise or amicable settlement are not admissible under this section as these must be taken to be conducted under the implied understanding that that they would not be given in evidence.

Explanation appended to the provision stipulates that this provision shall not be taken to exempt any barrister, pleader, attorney or vakil from giving evidence of any matter of which he may be compelled to give evidence Us 126.

Evidentiary Value of Admission:

There are two provisions regarding the evidentiary value of Admission:

- Admission not conclusive proof under section 31 of Indian Evidence Act, 1872

- Facts admitted need not to be proved under section 58 of Indian Evidence Act, 1872

- Admission not conclusive proof under section 31 of Indian Evidence Act, 1872:

An admission does not constitute a conclusive proof of the facts admitted (Sec. 31). It is only a prima facie proof. Thus, evidence can be given to disprove it. The admissions thus constitute a weak kind of evidence. The person against whom an admission is proved is at liberty to show that it was mistaken or untrue. But until evidence to the contrary is given an admission can safely be presumed to be true. The weight to be attached to it must depend upon circumstances under which it is made.

Union of India v Mokshi Builders (1977) 1 SCC 68]: Where a person was contending that he was not the real owner of a certain property but he had made statements before the Income Tax Officer that he was the owner of the property, it was held his admission was direct evidence of the fact of ownership.

Sec. 17 makes no distinction between an admission made by a party in his pleading and other admissions.

Bishwanath Prasad v Dwarka Prasad (1974) 1 SCC 78: An admission made by a person in plaint signed and verified by him may be used as evidence against him in other suits. There is no necessary requirement of the statement containing the admission having to be put to the party because it is evidence proprio vigore (of its own force). Thus, an admission in an earlier suit is relevant evidence against the plaintiff.

Admissions may operate as ‘estoppels’ under Sec. 31, Where an admission operates so, the party admitting the fact will not be allowed to go against the facts admitted. An estoppel will arise under Sec. 115 when the admission amounts to a representation that the fact stated is true and the other party has acted and altered his position on the basis of that representation. - Facts Admitted Need not be Proved [Section 58]: No fact need to be proved in any proceeding which the parties thereto or their agents agree to admit at the hearing, or which, before the hearing, they agree to admit by any writing under their hands, or which by any rule of pleading in force at the time they are deemed to have admitted by their pleadings: Provided that the Court may, in its discretion, require the facts admitted to be proved otherwise than by such admissions.

Conclusion

A statement made by a person mentioned in the sec 18 of the Evidence Act and, in the circumstances, mentioned in sec 18- 30 of the evidence act, which suggest an inference about the any fact in issue or relevant fact is an admission. It can be understood as anything a party has ever communicated either in speech, writing or in any other way in reference to the party at the trial is an admission. It is a positive act of acknowledgement of a fact or is a confession. It is not mere inference which is drawn by the any other act such as silence or implied consent. It must be conscious and deliberate act